2019-07-12

1. Introduction

One of the open questions in blockchain technologies is how to make a blockchain scalable so that it can support increasing numbers of both transactions and decentralized applications. There are many proposals for improving scalability such as lighting network[1], sharding[2,3], plasma[4]. A common idea they share is handling transactions in parallel. Sharding is the concept of dividing the network/computation/state into separate shards.

The challenge of sharding implementation is how to obtain information from other shards to verify the validity of cross-shard transactions. For example, if Darren in shard 1 sends some tokens to Max in shard 2, how could block validators in shard 2 know whether Darren has enough account balance? How to guarantee the safety of transactions? When it comes to smart contracts, the verification process is even more complicated because the validators need the state of smart contracts that is not easy to share in the network.

Seele mainnet with sharding implementation was launched on Mar 31, 2019. Besides sharding, it has a unique anti-ASIC MPOW consensus algorithm based on matrix computation. After running for a few months on the mainnet, the algorithm proves to be stable and decentralized. By far, considering the fact that there are not many nodes initially, Seele has 4 shards. Seele mainnet supports intra-shard transactions, cross-shard transactions and intra-shard smart contracts. Based on the statistics, in each shard, a block is generated every 14 seconds, which is close to the target block time: 10 seconds.

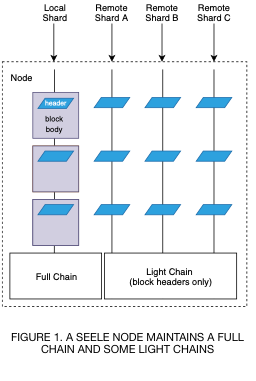

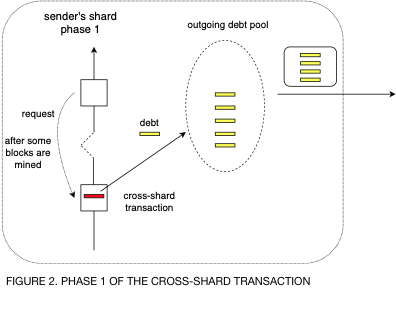

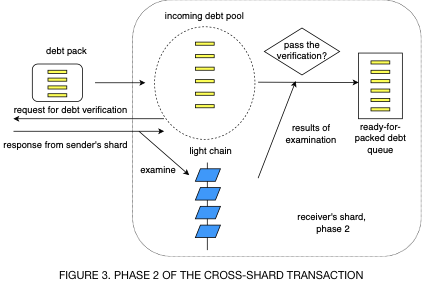

The basic idea of sharding in Seele mainnet is to partition the nodes and network into several shards. A transaction between two shards is called a cross-shard transaction. Because a cross-shard transaction involves accounts of two different shards, this transaction should be recorded in both shards. The transaction verification on the receiver’s side is a big challenge because validators in the receiver’s shard do not have the sender’s information at hand. They have to send requests to a remote peer to retrieve the desired information and carefully examine the responses. In Seele mainnet, we use light chains as archives of the other shards, with respect to the shard of the local node. The validity of the light chains is examined based on the POW solutions, which means it is impossible to forge a light chain without computation. If the responses from remote peers are consistent with the light chains, we have a high level of confidence that the cross-shard transaction has been confirmed on the sender’s side. But the maintenance of the light chains should not occupy too much resource such as CPU, storage and bandwidth. To this end, only the block headers are stored in the light chains. We will introduce more details in the next section.

2. Sharding

In this section, we will introduce how sharding works in Seele mainnet. At the setup stage, each node chooses a shard to join permanently. Nodes in the same shard share the full information including state, transaction history, etc., while nodes in different shard only share lightweight information such as block headers.

Transactions within a shard are relatively straightforward as all the information needed is accessible in a full chain. The logic of cross-shard transactions is more complicated because each Seele node only uses light chains to keep track of other shards.

With the above approach, it usually takes 20 minutes to complete a cross-shard transaction from subtracting sender’s balance to adding receiver’s balance.

3. Security analysis

In the receiver’s shard, block validators check whether the amount of debt has been deducted from the sender’s balance after a certain confirmation period. If the debt is forged by a malicious user, block validators can easily find out before it enters the incoming debt pool.

Since a cross-shard transaction is recorded on both the sender’s and the receiver’s shard, there are two possible inconsistencies. The sender’s balance is reduced but the receiver’s balance remains unchanged, or the sender’s balance remains unchanged but the receiver’s balance is increased.

The first scenario is not going to happen in Seele mainnet. As long as the transaction is recorded on the sender’s side, the nodes in the sender’s shard will send out the corresponding debt again when a certain condition is met. Therefore the receiver’s shard always has a chance to record the transaction. The second scenario could lead to an inflation of the whole Seele mainnet. But for this scenario to happen, attackers needs to create a malicious long fork in the sender’s shard. This kind of attack is difficult because Seele’s MPOW algorithm[5] is anti-ASIC and there is an additional mechanism in Seele mainnet to check the consistency of cross-shard transactions.

4. Conclusion

With 4 shards, Seele can achieve around 2000 TPS at peak which already meets the needs of many Dapps. Additionally, more shards can be added to Seele mainnet. But more shards mean a higher requirement for network connection. In the future, Seele is going to combine its sharding with subchains to achieve a more scalable system.

5. References

[1] Joseph Poon, Thaddeus Dryja. The Bitcoin Lightning Network: Scalable Off-Chain Instant Payments. 2016

[2] Ethereum. https://github.com/ethereum/wiki/wiki/Sharding-roadmap

[3] Loi Luu, Viswesh Narayanan, Chaodong Zheng, Kunal Baweja, Seth Gilbert, Prateek Saxena. A Secure Sharding Protocol For Open Blockchains. 2016

[4] Joseph Poon, Vitalik Buterin. Plasma: Scalable Autonomous Smart Contracts. 2017

[5] Luke Zeng, Shawn Xin, Avadesian Xu, Thomas Pang, Tim Yang, Maolin Zheng. Seele’s New Anti-ASIC Consensus Algorithm with Emphasis on Matrix Computation. 2019